SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf

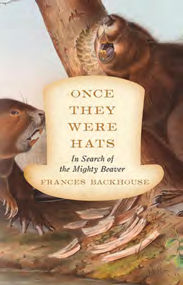

"Once They Were Hats: In Search of the Mighty Beaver"

By Frances Backhouse

ECW Press, $16.95

Reviewed by JENNIFER WEEKS

Many of us have never seen a beaver in the wild. But if you are driving through a wooded area and pass ponds studded with dead trees drowned by rising waters when beavers built dams nearby, you have seen their work.

Known as nature’s little engineers, beavers have been shaping the North American landscape for at least one million years, possibly as long as 24 million years.

In “Once They Were Hats: In Search of the Mighty Beaver,” SEJ member Frances Backhouse explains how dramatically beavers have sculpted our landscapes — and why we need them today.

Before European explorers started coming to North America, at least 60 million beavers lived in nearly every part of the continent.

They built some 25 million dams, which created ponds and wetlands that later evolved into meadows. Numerous plants, animals and birds grew to depend on habitats created by beavers.

Backhouse calls beavers “the indispensable creator of conditions that support entire ecological communities.”

Indigenous North Americans killed beavers for meat and fur. But hunting took a much heavier toll starting in the late 1400s, when European fishermen started sailing into North American waters and trading with native peoples.

Beaver fur, which is extremely dense and water-resistant, soon became a prized commodity, especially for making hats. “A wool hat doesn’t keep its shape in [wet] weather. It just folds,” a modern hatmaker tells Backhouse. “But beaver’s great. The best hat we could ever make is beaver.”

By the early 1600s, French, English and Dutch forces were competing for control over the beaver pelt trade and killing beavers at unsustainable rates. In 1856, Henry David Thoreau noted in his journal that beavers and other large mammals were largely gone from New England.

Beaver populations bottomed out at a few hundred thousand in the early 1900s, then started a slow recovery, spurred by limits on hunting and trapping. Today, scientists estimate there are roughly 10 to 50 million beavers across the continent.

Meanwhile, hydrologists have found that beavers can have profound effects on water supplies.

Water seeps down into the earth from beaver ponds, recharging groundwater and raising the water table. This underground supply helps drought-proof the land above it — a valuable impact in places that are becoming drier as a result of climate change. Some national parks in the United States and Canada are introducing beavers as a water management strategy.

“Once They Were Hats” takes readers to many places, including remote Canadian forests, a trapper’s lodge (where Backhouse skins a beaver) and a modern fur auction house. Backhouse also talks to First People who recount beaver legends and to park managers who have to manage flooding caused by beaver works.

While many landowners see beavers as pests, Backhouse takes a different view. “The problem is not that there are too many beavers,” she wrote. “It’s that while they were absent, we humans took over a large portion of their habitat. More often than not, we see returning beavers as interlopers, instead of recognizing them as an integral part of how our hydrological and ecological systems work — or should work.”

She adds: “We need to cure our amnesia, rethink our relationship and acknowledge how much we stand to gain by engaging beavers as keystone partners and climate-change allies.”

“Once They Were Hats” makes a strong case for welcoming beavers back to the job.

Jennifer Weeks is a Massachusetts-based freelance writer and former SEJ board member.

* From the quarterly news magazine SEJournal, Spring 2016. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement