SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

December 6, 2016

Feature: Green Burial Not Just Throwing Ashes on Compost Heap

By Ann Hoffner

|

| For author Ann Hoffner, the green burial of her father after his death this summer brought home the deeper meaning of the environmentally centered ceremony. Photo: Tom Bailey |

Five years ago the problem of conventional burial of human bodies meant nothing to me. I was living aboard a sailboat with my husband, photographer Tom Bailey, never lacking for a story about meteorology on the high seas or an exotic destination.

Then we left our vessel Oddly Enough in Northern Borneo and took a break from sailing to help my aging parents, and I became paralytically afraid that on land I'd never find anything exciting to write about. One day, as I idly searched the Internet for recycling information on the clear plastic boxes that I’d noticed were packaging everything from lettuce to cut fruit, the unfamiliar term “green burial” cropped up.

My stumbling upon the term ultimately led to a years-long project to compile a complete guide to natural burial cemeteries in the United States.

In case you don’t know, green burial is a way of disposing of a dead body without formaldehyde-based embalming or environmentally unfriendly concrete burial vaults, and in a shroud or biodegradable casket. It also means using minimal heavy equipment for burial and landscaping in a cemetery where the gravesite is part of a reclaimed or existing forest or meadow that is maintained with minimum intervention and is marked with an engraved fieldstone or no marking at all.

Some argue that this is the way Americans buried their dead until the Civil War, when modern embalming techniques were perfected. But green or “natural” burial (they have slightly different emphases) is a more deliberate and relatively new choice.

After Jessica Mitford focused attention on the "American way of death" in 1963 with her investigation into the funeral industry, cremation became the accepted alternative to conventional burial. While it is simpler, its virtues as a better choice for the Earth are being debunked just as the creaking funeral industry is finally embracing it.

|

| Photo: Tom Bailey |

A concept made personal

When my father died suddenly in August I knew I was going to bury him naturally, as he and I had discussed. But as his funeral director reminded me, "You can think you know all about green burial but until you experience it, you don't."

While more natural burial cemeteries are coming online, none is very close to me. But I did know Bob Prout, a funeral director here in northern New Jersey, a green burial advocate since 2007 when there were just a handful of such places, and someone I’d previously interviewed for two green burial reporting projects.

After I took my unconscious father to the hospital and found out he had days to live, my husband and I saw Bob on the other side of his desk, as it were. The wall video screen Bob uses to review costs and schedules with consumers showed the photo he took of autumn fields at Greensprings Natural Cemetery Preserve outside Ithaca, N.Y., from his hearse window after a natural burial there. Bob uses it to start the conversation.

"Nice screensaver.""It's a cemetery.""Noooo."

In the end, our cemetery of choice was Steelmantown, two hours away in South Jersey. That added in some fossil fuel usage but made sense because my mother's family lives ten minutes away on the ocean side of the Garden State Parkway.

Ed Bixby, Steelmantown's owner, had found the historic cemetery overgrown and unwanted when he had gone looking for his infant brother’s burial place. He bought it and developed 8.5 acres of adjoining woods as a natural burial cemetery.

The first time Tom and I made the trek to Steelmantown we almost turned around at the sight of three men, two old, one young, in combat boots and camo and duck-tailed haircut, and a dog, all sitting on a log next to a pickup truck. This is New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, where suburban Northerners are told strange people called “pineys” live.

Luckily we stayed and we fell in love with Ed's Eco Trail, winding through oak woods and connecting up to a section of Belleplain State Forest that until now had been landlocked.

I'd already experienced the first thrill of looking at a spot of earth and realizing that under the mound was a new unembalmed body jumbling up its bones with the soil. Ed, of course, knew his cemetery like a science experiment; mound “a” was a month old, mound “b” a year old, mound “c” (unrecognizable from the forest floor) three years old.

I'd already experienced the first thrill of looking at a spot of earth and realizing that under the mound was a new unembalmed body jumbling up its bones with the soil. Ed, of course, knew his cemetery like a science experiment; mound “a” was a month old, mound “b” a year old, mound “c” (unrecognizable from the forest floor) three years old.Natural graves generally are mounded with the dirt that comes out, since unlike a conventional steel casket in a concrete vault its contents are meant to decompose back into the soil and the dirt settles down to fill the resulting space.

‘I finally understood the point of green burial’

On the day of my father's burial I drove down with my brother and nephew. By the time we got there I was so nervous I could barely function. People were pestering me about a toilet. I had to go myself and I knew the way to the outhouse, a sweet smelling wood cubicle next to the replica chapel. As I sat on the box my anxiety fell away.

It was 92 degrees and just after midday. The air sang with heat as we gathered on the path; thirty people including mourners and Ed's gravediggers. Bob, wearing a tie, and Ed, in his boots, gathered us in. Bob suggested that I ask people to take their flowers out of the cellophane they were crinkling, then gave an eloquent synopsis of what would happen next.

My father was not alone.

As soon as he went into the ground,

he was joined by the beetles,

the worms, the bacteria, tree roots.

The source of my anxiety had been how people would react to a shrouded body so I was grateful for his introduction. Then as a gravedigger and Ed took hold of the handles on the wagon-wheeled cart on which my father lay, covered in a flag and wildflowers, Bob suggested I help push from the back.

So began the slow procession over the winding moss-covered path, lumpy with tree roots. The wagon wheels creaked out a melody and the sweat trickled down my back. We halted by a mound of dirt with shovels sticking out that covered the plot we purchased for my mother.

I envisioned a natural burial as being loose and spontaneous, but Bob had prodded us into a structure for which I was grateful. It was capped by the military honor guard folding the flag and playing gorgeous taps while a Monarch butterfly looped restlessly over the open grave. Six people lowered my father's shrouded body in a big muslin cloth into the grave and let the muslin fall over him.

We took turns tossing flowers and pine boughs to join those that lined the grave bottom. Ed and his father passed out shovels. My 21-month-old grandnephew in his sun suit was so excited. "Big shovel," he cried out as he helped his mother throw in the sandy soil.

I didn't speak myself, and as others read or told stories I let the sun filtering through the woods dry the sweat on my upturned face and I felt the listening weight of all those trees.

I didn't speak myself, and as others read or told stories I let the sun filtering through the woods dry the sweat on my upturned face and I felt the listening weight of all those trees.It seemed much longer going back to the sheds with the empty cart. Ed piles fieldstones dug up from his property and we chose a long flat gray one that would reach across two side-by-side graves. Bob and his assistant were shedding their ties. I invited them all to join us at my cousin’s house for a meal but they wanted to get home before the end of weekend traffic rebuilt.

That night I thought about a cousin who was buried just the weekend before in a conventional memorial park in a painted metal casket in a concrete vault under an Astroturf temporary covering — and I realized that my father was not alone.

As soon as he went into the ground, he was joined by the beetles, the worms, the bacteria, tree roots. The night crickets and owls. The wild blueberries that had been pulled back to admit his body and would be replanted. It was an extraordinary realization that he had joined an ecosystem. And because he couldn't move it would come to him. It would recycle the nutrients in his flesh and bones and weave them into life.

And that, I finally understood, is the point of green burial. As much as it is an end, it’s also a precursor to life.

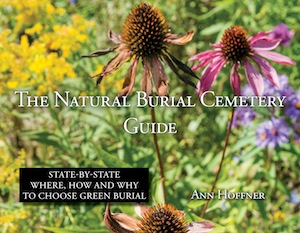

After spending ten years in a 44-foot sailboat, travelling with her husband down the Panama Canal, across the Pacific to Australia and Southeast Asia and writing freelance articles for sailing magazines, SEJ member Ann Hoffner is living and writing back in the States, investigating environmental topics like natural burial and recycling of plastic food containers, and creating digital books. Learn more about her soon-to-be-published "The Natural Burial Cemetery Guide" on her web site.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 1, No. 6. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

SEJ Publication Types:

Topics on the Beat:

Region:

Visibility: