SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

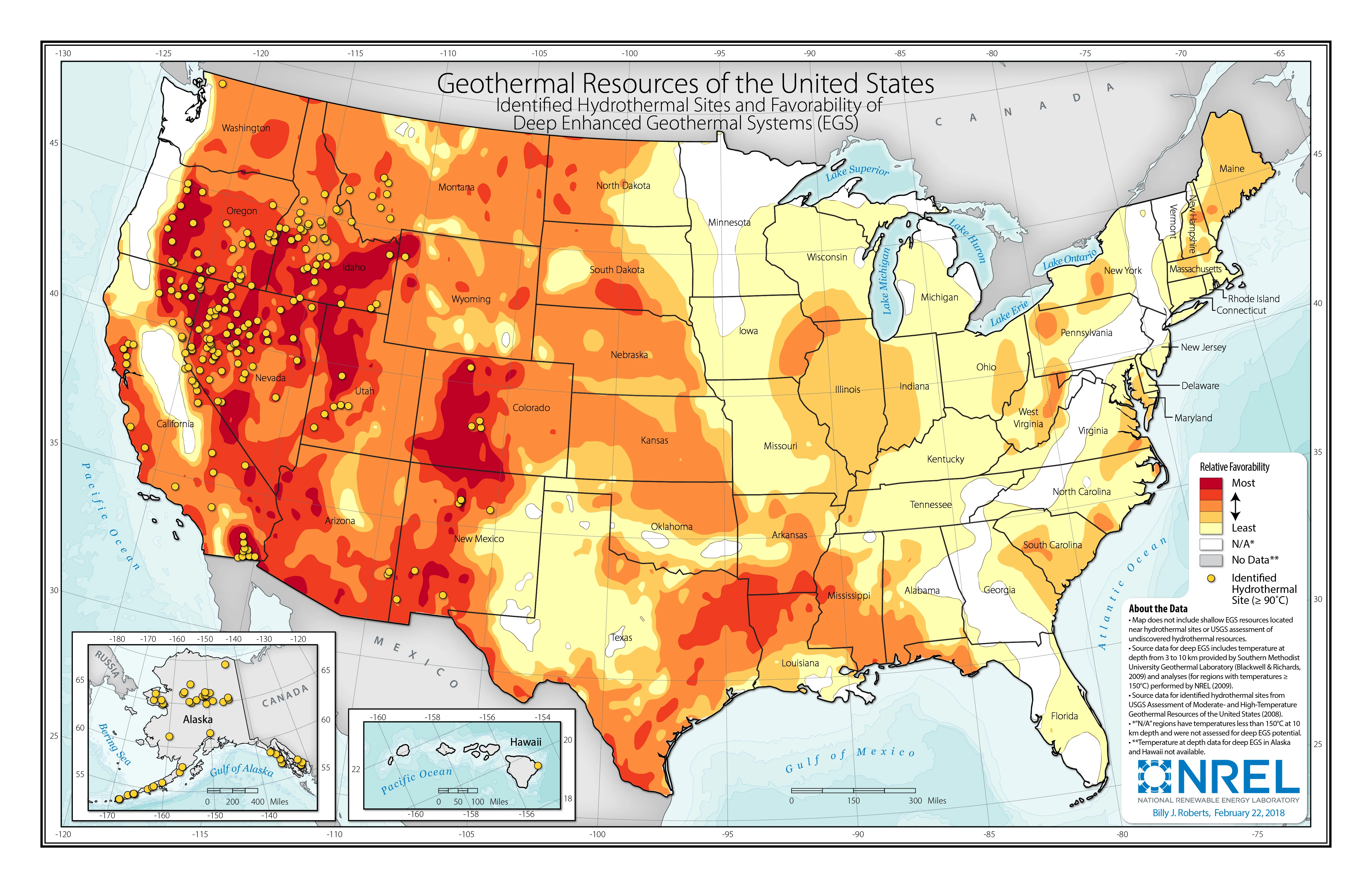

| A map showing geothermal resources across the United States. Image: National Laboratory of the Rockies. |

Backgrounder: Geothermal a Valuable, But Overlooked Clean Energy Source?

By Joseph A. Davis

In some parts of North America, you can drill for clean energy.

If you have been to Yellowstone National Park, you may be familiar with the geothermal resources there: surface features like mud springs, fumaroles and Old Faithful. Although these are visible to pedestrian tourists (stay on the boardwalk), their heat comes from hot rock thousands of feet underground.

The higher-tech version of geothermal works by drilling wells deep enough into the Earth’s crust to find hot rocks or hot water. Heat is transferred from underground via hot water (or steam) in pipes. It is ultimately turned into steam that drives turbines that drive electric generators.

Systems like this are operating in the U.S. right now. Oh — and it doesn’t produce climate change. Or hardly does, to be precise. In practice, there is often a lot more to it.

Meanwhile, neighbors on your block may have already installed heat pumps to warm and cool their houses. This, too, is a form of geothermal energy.

A lot of news outlets

these days are announcing that

geothermal is an energy source

whose time has come.

So a lot of news outlets these days are announcing that geothermal is an energy source whose time has come (subscription required). Maybe so, but it’s still rare in the mainstream economy.

And environmental reporters often overlook geothermal as a solution to the problem of greenhouse gas emissions.

Seeking surface heat

The deeper you go, the more heat there is. The Earth’s solid iron core is about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is roughly the temperature of the sun’s surface.

The biggest fraction of that heat comes from radioactive decay, while the rest is left over from Earth’s fiery origins.

Wells drilled by humans barely reach the beginnings of the mantle — just a few miles down. If you drill down only a mile, you will find temps between 100 F and 140 F. Depending.

There is a lot of variation from place to place, and geothermal usually makes most sense in places where the heat is closer to the surface.

Utility-scale geothermal, and smaller scale, too

You can find on-the-ground proof of concept a few hours north of San Francisco if you visit Calpine’s The Geysers geothermal facility — the largest in the world.

Thousands of years ago, Native Americans had used the heat from The Geysers for cooking, healing, and spiritual and ceremonial practices.

Today, the Geysers is a

complex of 13 geothermal

power plants, which get steam

from more than 350 wells.

Today, the Geysers is a complex of 13 geothermal power plants, which get steam from more than 350 wells. The plant can produce 725 megawatts around the clock — enough electricity to power 725,000 homes, or a city the size of San Francisco.

“Geothermal,” technically speaking, can also power some of the heat pumps that are being installed at many U.S. homes and businesses. Some of those connect to “ground loops,” a feature used in HVAC systems for smaller scales. These may be as little as six feet deep — a depth at which temperature is constant.

Ground loops act as a heat sink when aboveground temperatures are warmer and as a heat source when aboveground temperatures are cooler. But not all home heat pumps have ground loops. It’s complicated.

Uninterrupted source, but with some drawbacks

|

| The Cal Energy Generation geothermal power plant in Imperial, California. Photo: Kevin Key via Flickr Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). |

One of the very nice things about geothermal generation of electricity is that it is steady and relatively uninterrupted.

That sets it apart from some other renewable energy sources like solar photovoltaic (which only produces when the sun shines) or wind turbines (which only spin when the wind blows).

Peak demand for electricity doesn’t always happen at these times. Geothermal can provide the grid with baseload — the key need now met by fossil fuel and nuclear plants. The gas companies will not let us forget this.

Geothermal has drawbacks, too. Initial costs are usually high. The more drilling needed, the higher they go.

The technology used to turn hot water or steam into electricity quickly gets expensive as well. Most installations turn heat and water into steam, and use the steam to drive turbines. And then they use more technology to make use of spent steam for heating buildings — or even whole towns through district heating systems.

Another drawback of

big geothermal is

that it is not easily

available everywhere.

Another drawback of big geothermal is that it is not easily available everywhere. It makes more cost-efficient sense where we find it relatively close to the surface.

Yet another drawback: Years of hot steam can corrode and wear out equipment quickly. Replacement creates more costs.

Another challenge is that hot geothermal water can contain dissolved contaminants leached from minerals deep underground. They may include mercury, arsenic, boron, antimony and salt.

Those may cause problems with equipment or generate removal costs unless they are pumped back underground.

The worst contaminants may be carbon dioxide or methane, greenhouse gases that may require removal to prevent release to the atmosphere.

The binary cycle solution

In reality, many larger-scale geothermal installations today use technology called “binary cycle.”

That means after steam is used to drive turbines, the spent steam or hot water is then used for other things (from soothing hot baths to de-icing sidewalks to building and district heating). As it reuses heat, it is analogous to what gas electric plants call “combined cycle.”

Key point: More technology means more equipment to pay for, to go on the fritz or to replace.

Geothermal installations often consist of multiple pipes and drilling operations. More wells can deliver more heat. Spent water may be returned underground to be heated again. More wells, more costs.

World leaders in geothermal

Right now, the United States leads the world in geothermal generation. We produced 16.24 terawatt-hours of power in 2021.

Other nations among the top geothermal generators include Indonesia, the Philippines, Turkey, New Zealand and, of course, Iceland.

The International Energy Agency says investment in geothermal is growing (although a significant portion of geothermal heat used worldwide is not used for electric generation).

The IEA says one of its advantages is that it is secure and stable — compared, for example, to oil — because the price of the actual energy source does not go up or down and because it cannot be interrupted by a Mideast boycott.

One final bit of good news about geothermal: Much (not all) of the drilling technology is already familiar to oil and gas companies. Parts of the oil and gas industry, should they ever become underemployed, may welcome this.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's TipSheet, Reporter's Toolbox and Issue Backgrounder, and curates SEJ's weekday news headlines service EJToday and @EJTodayNews. Davis also directs SEJ's Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 11, No. 3. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement