SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

Author Michael Kodas explores the burn zone of the Sunshine Fire that nearly burned into Boulder in March of 2017. Kodas was leading a field trip of environmental journalism students and fellows through the fire scene. PHOTO: Joanna Pinneo

|

Between the Lines: Forged in Fire — Author Follows the Flames, and Fights Them, To Cover the Changing Nature of Wildfires

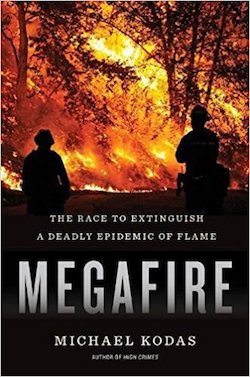

In his upcoming book, “Megafire: The Race to Extinguish a Deadly Epidemic of Flame,” SEJ member and forest fire expert Michael Kodas explores the global rise in recent years of these large-scale, intense and devastating fires and offers insight into the dangers for those who fight them. Kodas, an award-winning photojournalist, author and associate director of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado, Boulder, went all over the world for his research. He spoke with SEJournal BookShelf editor Tom Henry for this latest installment of Between the Lines, an author Q & A.

SEJournal: What inspired you to write “Megafire”?

Michael Kodas: I became interested in the growing wildfire problem back when I worked at the Hartford Courant, when I learned that a number of employees of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (now the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection) spent part of their summers working as firefighters for the U.S. Forest Service in the western United States. I wondered how the fire problem had grown to the point that the federal government was recruiting crews of firefighters from state government departments in areas of the country with less of a wildfire threat. I wanted to tell that story. The only way to do it the way that I wanted to do it was to train and join one of those crews, so that’s what I did. I spent several weeks fighting fires in Colorado and Wyoming with a crew of firefighters from Connecticut.

A few years later, I read a story in Nature that showed a fourfold increase in the number of fires and a sixfold increase in the amount of land burning compared to 16 years before that. A couple of years after that, I learned that 60 firefighters with the National Park Service were called up on 48 hours notice and sent to fight the Black Saturday fires in Australia, where nearly 173 people perished. As I conducted my research, I came to have a very different idea of what constitutes a “megafire” than the one I started out with. I came to define megafires by their impacts rather than their size, heat or speed.

'Climate has also led to fire behaviors that

firefighters claim they’ve never seen before.'

SEJournal: Is there evidence to show — or, at least strongly suggest — a direct correlation between the rise of megafires over the past 20 years and climate change?

Kodas: Research by Leroy “Tony” Westerling in California, Tom Swetnam in Arizona and several other scientists show a distinct increase in the size and frequency of wildfires since the middle of the previous century. There are several drivers — and climate is definitely a big one. There’s some research to show that rising temperatures will bring an increase in lightning strikes to start wildfires naturally, but the biggest impact of climate on the current fires in the West is [lack of] snowpack. Snow high in most western mountains historically lasted well into summer and as it melted it kept the forests below moist and less prone to burn. But the changing climate has led to less snow falling in many regions and to that snow melting off earlier in almost all mountainous regions of the United States.

The subsequent earlier drying of mountain forests has led to a two-month increase in the length of fire seasons in much of the mountain West. Hotter and drier conditions make vegetation easier to ignite and drive it to burn faster and hotter. Climate has also led to fire behaviors that firefighters claim they’ve never seen before, such as fires burning intensely through the night. Nights used to cool off more, which would lead to increasing moisture in the air that would cool and calm fires after the sun went down. That happens less frequently now.

|

| An inmate at an Enfield, Conn., prison running to escape a grassfire that nearly burned him over in 1986. The photo was the first Kodas had published from a wildfire. PHOTO: Michael Kodas |

Development and expansion of human infrastructure puts many lives, homes and resources at risk, and also increases the incidence of fire. Research this year by Jennifer Balch here at the University of Colorado showed that in the 1990s and 2000s, 84 percent of wildfires were started by humans. Most people think of arson, but those make up a small percentage of human ignitions of wildfires. Arcing power lines, sparks from machinery and vehicles, firearms and even golfers striking rocks in exceptionally dry roughs have started wildfires. What’s more, humans start 100 percent of wildfires at the times of year when there’s no lightning to start them naturally.

Those seasons are also when the government is least prepared for the fires. Seasonal firefighters are furloughed and back in college. Equipment is in warehouses because it’s too expensive to keep it available year-round. Finally, humans add their own fuels to the woods. When I first trained as a wildland firefighter, we just learned about how to deal with burning trees and grass. Today, the federal government educates firefighters about what to do if they come across a meth lab or a shed full of chemicals in the woods.

SEJournal: Most everyone who lives in a city is in awe of local firefighters willing to enter burning homes and office buildings to save people. But forest fires are another animal. Since you've been out on the front lines, what can you tell us about firefighter strategies out in the wilderness?

Kodas: Forest fires are indeed very different from burning buildings, but the development of the “wildland urban interface,” or “WUI" — the region where development abuts forests and other flammable landscapes — has led to an increasing amount of overlap between the two types of fires. The number of homes burning in wildfires today is seven times higher than it was in the 1970s, and a 2015 study from the U.S. Forest Service reported that one in three U.S. residences — some 44 million homes — is in the WUI. So wildland firefighters are increasingly going to have to deal with the kind of challenges which structure firefighters face.

This came home to me when I was investigating the death of the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots in the tragedy at the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona in 2013 — the largest loss of life among professional, wildland firefighters in U.S. history. A half hour before they died, the firefighters who perished were in a safe area that firefighters call “the black,” where most of the vegetation had already been burned away by the fire so there was little risk the blaze could reach them there. But when they were burned over, they were in a box canyon so thick with chaparral that any firefighter would recognize it as a death trap. There were no survivors, so we’ll never know for sure why the firefighters took such an incredible risk. But beyond the canyon where they died, the town of Yarnell was being burned over and the Granite Mountain crew had been asked to join the firefighters trying to save the town. It’s pretty easy for a crew to step back from burning trees in a forest fire when the situation gets too dangerous, but far more difficult to let homes burn, particularly when the firefighters may know some of the homeowners, which was the case with the Granite Mountain Hotshots.

'The basic work of wildland firefighting

hasn't really changed in a century.'

Structure firefighters wear heavy “bunker gear” to protect themselves from the flames, have oxygen masks they can wear in thick smoke, ride in fire engines to the blaze and have abundant water to extinguish the flames in burning buildings. Wildland firefighters have to walk miles to the scene of the fire, so they wear lightweight, fire-resistant clothes and carry no oxygen equipment or heavy fire coats. Their primary suppressant is dirt, which they shovel on flames while digging a perimeter known as a “fire line” that’s cleared of vegetation around the blaze, thus corralling the fire.

The basic work of wildland firefighting hasn't really changed in a century, but there are many impressive technologies such as portable weather stations, satellite data, drone reconnaissance and cameras that can see the fire and its heat through the smoke. The most visible technology is in the airpower mustered to fight a fire. But it’s important to note that the dramatic red slurry being dropped from airplanes is a fire retardant, and doesn’t extinguish the flames. Everything covered with the retardant will eventually burn if firefighters can’t march in and put out the fire there with shovels, axes and chainsaws. Estimates are that less than 30 percent of retardant drops from aircraft have any impact on the final size or destructiveness of a wildfire.

|

What’s more, aerial firefighting is incredibly dangerous. The airplanes used to fight fires aren’t built for that purpose, and they regularly crash due to conditions that exceed the stresses the airframe was designed for. Firefighters' chances of dying on the job go up tenfold the moment they step into an aircraft. Most wildfires are wind-driven events, so when a fire is blowing up and the public and politicians most want to see aircraft trying to stop it is when aerial firefighting efforts are most dangerous and least effective, since the winds make flying more difficult and often blow away fire retardant and water before it reaches its intended target. Finally, the incredible cost of firefighting aircraft has led to a number of scandals in aerial firefighting programs, some of which have led to the deaths of firefighters.

SEJournal: How did you balance the drama of fighting huge forest fires without getting too emotional as a writer? How important is tone to this book and — for a subject like this — is it best told as a thriller or science book?

Kodas: I’ve tried to balance this book between exciting narratives and science-based reporting. The increase in wildfire affects millions of people and most of them aren’t interested in reading about science, even when it so directly affects their lives. Storytelling elements — narratives, great characters, drama, rising tension — are kind of candy coating. If you can get a reader hooked with the narrative, you can build momentum that will carry them through the drier, scientific data and help them remember the important facts.

SEJournal: You once thought of wildfires as "natural disasters," but became convinced they "are not natural at all, rather the results of political, economic, social and cultural decisions." Why?

Kodas: Wildfires are as natural a part of vegetated landscapes as rain. The cycle of fire is an important part of the health of most forests and grasslands. One irony is that, while we’re seeing more and larger wildfires, many of our vegetated landscapes suffer from a "fire deficit" that’s deteriorated their health. So while we’re fighting more fires, we’re also trying to “re-introduce fire" to many landscapes where we suppressed too many fires, because they need fire to make them less prone to excessively hot and uncontrollable megafires. Some creatures — the black-backed woodpecker, for instance — are dependent on severely burnt forests for their habitat.

|

|

Kodas at the Bluebird Fire in Colorado in 2003 during the summer he worked as a wildland firefighter for the U.S. Forest Service in order to report on the increasing frequency and size of wildfires in the western United States.

|

Even the biggest and hottest forest fires aren’t considered disasters until they put human values at risk, due to decisions that we’ve made as societies. The government created dozens of incentives for developers to build homes deeper and deeper into flammable landscapes. Along with the homes came reservoirs, power lines and many other societal values, all of which are threatened by the wildfires that would naturally burn through these landscapes. So we have increased incentive to put out wildfires, even though many of these forests need to burn and — one way or another — are going to burn.

SEJournal: How does a would-be author know when a body of evidence exists to make a compelling argument for better accountability? Are there parallels between how we think of the rise of mega forest fires and the rise of mega hurricanes as they relate to climate change?

Kodas: The comparison of wildfires to other natural disasters is interesting — particularly because, as a society, we don’t think of wildfires in the same way we do other forces of nature. We don’t have earthquake fighters, or hurricane fighters, or tornado fighters, but we have wildland firefighters whom we expect to take on something that is, effectively, a weather phenomenon. And we’re killing them at twice the rate we did 40 years ago. As we put more and more homes and values in flammable landscapes, I think it’s important to inform the public that its choices of where to live, what to build and how it manages land have real impacts on the lives of people who don’t reap the benefit of those lifestyle choices.

On top of the human toll, there’s a financial toll that impacts every U.S. taxpayer. In the early 1990s the U.S. government spent about $300 million a year preparing for, fighting and recovering from wildfires. Today, that figure tops $3 billion. In 1995, about 16 percent of the U.S. Forest Service budget was spent on wildfires. In 2005, fires took up 52 percent of the Forest Service’s budget. U.S. Forest Service scientists predict that the changing climate and other drivers of the increase in wildfire will lead to 20 million acres of the U.S. burning in bad fire years by the middle of this century. That’s an area equivalent to the entire state of Maine.

SEJournal: What advice do you have for would-be authors about planning and executing a book, especially on such a broad topic as megafires?

Kodas: We’re seeing our planet and the issues that affect it changing at such an incredibly fast rate. It’s important to produce projects that are topical and up to date. To that end, here are few pieces of advice:

- Look for trends in the scientific literature. Develop relationships with researchers who can advise you of developments in science even before their research is published.

- “Use the whole animal.” There are a ton of stories that I couldn’t fit into the book, but many of them appeared in magazine or newspaper stories, or in various documentary and multimedia projects that I produced while working on the book.

- And trust your gut. If you think you’ve got something that will make a great book, or other long-term project, commit and go after it with passion. The fact that editors or agents don’t see it could be an indication that you’ve got a good head start on a trend.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 2, No. 25. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.