SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

BookShelf: Between the Lines — Writing Nature Through Illness and Disability

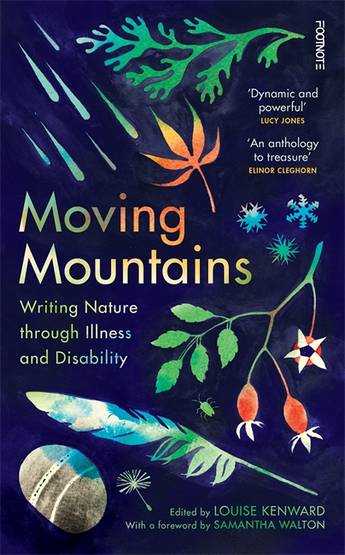

For the latest edition of our occasional Q&A series, “Between the Lines,” SEJournal contributor William Allen interviewed editor Louise Kenward about the groundbreaking book, “Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability” (Simon & Schuster, $14.95). The book is an anthology of nature writing — prose, poetry and more — by contributors who engage with the environment through different lenses than the nondisabled. Originally published in London in 2023, the book was released in North America in May 2025. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

|

SEJournal: As you write in the introduction, “Moving Mountains” presents a range of voices that “have gone unheard, or indeed been silenced,” and “have valuable and important contributions to make” to nature and environmental writing. What distinguishes this anthology from others?

Louise Kenward: The book focuses specifically and entirely on authors who live with chronic illness and/or are physically disabled. I wanted to center particularly on physical disability, although mental health and neurodivergence are also represented in the anthology, but were not the central themes. In practice, it isn’t possible to separate out these things entirely because we all live in just the one body, and there is so much complexity and interweaving of mental health and physical health. But my aim was to center the people who might not ordinarily be regarded as engaging with the natural world due to barriers or expectations. I wanted to bring a collection of new knowledge to the field of nature writing, of experiences that might typically be overlooked or unseen in writing about the outdoors.

SEJournal: The book is literature; it's intriguing, creative, fun to read, sometimes heartbreaking. There’s an artistic bent. It's also an education for those of us who haven't thought about these perspectives before, of other ways of looking at the environment, at nature. What is the overarching message here?

Kenward: I hope the anthology shows that 25 different disabled and sick authors will write 25 different accounts of illness and disability, and they will write 25 different accounts of their connection with the natural world. It makes for a much more colorful portrayal of nature as well as people inhabiting it. Its message is that the portrayal of illness and disability is richer and more interesting than might be expected.

SEJournal: Chronic disease and illnesses come in many forms, including heart disease, diabetes and chronic fatigue syndrome. In the United States alone, chronic diseases affect upward of half of people. What kind of illnesses and disabilities are represented among the contributors?

Kenward: I specifically didn’t ask anyone to self-disclose their condition or diagnosis, as society can be so intrusive when you live with illness and disability anyway — having to justify requesting accommodations or financial support, for instance. Many of the contributors have written about this, though, including several energy-limiting illnesses, like mine. For example, several live with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), where post-exertional malaise is the defining symptom. That means that you can do something that might seem simple to anyone else, like going for a walk or washing your hair, and depending on the person and the day, the consequences of that action can far outweigh what you might ordinarily expect, causing debilitating fatigue and flaring of other symptoms. It can last for days, weeks, months. Some people don't recover, and they find a new level of disability after what had seemed a relatively minor exertion.

Kate Davis has written about the impact of having polio as a child. Carol Donaldson writes about her experience of migraines. Isobel Anderson writes about how she could walk a long way but couldn’t sit down because the pelvic pain was utterly debilitating. Some have connective tissue disorders, a genetic condition of the quality of collagen in the body, which can affect any number of systems, typically gastrointestinal, joints and ligaments. This includes hypermobile conditions like mine, and hEDS (hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome), which Polly Atkin and Victoria Bennet have written about. And Kerri Andrews writes about her experience of genetic hemochromatosis. Themes of pain and fatigue are common throughout the book, reflecting the commonality of these symptoms in so many illnesses and disabilities.

SEJournal: What do you hope readers gain from the book?

There is a kind of kaleidoscope of

different lenses to see things through

— each one intersecting with the other.

Disability is just one.

Kenward: Many different things. There's an enormous amount to be gained if you recognize elements of yourself in the people in the book, of solidarity and companionship. And for people who don't live with a disability or haven’t had a chronic illness, it shows the diversity and richness of human experience as well. We can learn much from each other. There is a kind of kaleidoscope of different lenses to see things through — each one intersecting with the other. Disability is just one. More than anything, I hope that readers come away with more compassion for one another and the world around them.

Disabled people often experience the repercussions of things first, because we may have more vulnerable bodies or are more sensitive to environmental changes, such as heat intolerance or sensitivity to chemicals or mold. Society may see that as just a problem of an unusual group, a marginalized group. But we’re often like the canary in the coal mine. Something may not yet have had an impact on the general population, but it’s a clue as to what's coming. COVID-19 has shown us that. For decades, people with ME/CFS, often triggered by a virus, have warned of the harm of post-viral illness, but it was not until millions more people were affected by long COVID (many going on to be diagnosed with ME/CFS) that the knowledge people with ME/CFS already had was played out in such a clear way.

I’d love nothing more than to prevent more people becoming disabled in this way, but it is very difficult to be heard and understood with an overwhelming pressure to “get back to normal” and for “COVID to be over” — whether it is or not. I hope “Moving Mountains” helps in some small way to promote this kind of knowledge, so that prevention (like face masks and HEPA filters) could become more standard practice to prevent airborne viruses — just as clean water is now seen as essential in preventing waterborne infections (like cholera).

SEJournal: The problem of climate change imbues some of the pieces. What drives that connection?

|

| Author Louise Kenward |

Kenward: The climate crisis is enormously important for disabled people. We are typically the last to be considered in things like disaster planning and the impacts of climate change. And yet, we're likely to be the first population affected. For instance, people who are disabled and chronically ill will be hit harder by rising temperatures. Many of us can't function beyond a certain temperature. Similarly, pollution and smoke from wildfires affect people more severely if they already have difficulty breathing. Considering disabled people in terms of the climate crisis and environmental crisis is essential.

SEJournal: I was especially impressed by “Abi Palmer Invents the Weather,” in which the artist (Abi Palmer) creates elaborate boxes — environmental sculptures, really — for her two indoor cats to explore. She addresses them as “friends,” wants them to learn about the natural world and expresses her worry about the climate crisis. She writes that part of surviving the crisis “is to actively care for the small spaces within our reach.”

Kenward: It is a brilliant piece. It consists of transcriptions of four of her short films, “Abi Palmer Invents the Weather,” along with an introductory essay and photographs. The films are on tour across Europe. It’s fascinating how she “invents” the weather, and the relationship between her and her cats is utterly charming. She manages to talk about huge issues of the climate crisis and grief through really playful, poetic ways.

SEJournal: The contribution from Sally Huband, “Field Notes,” resembles a classic take on a wanderer along a shoreline, in this case near her home in the Shetland Islands of northern Scotland. But her poetic prose features the interplay of nature and body pain. For example, the “stealthy” east wind “finds, with great accuracy, the places under my skin where pain hides.” In another passage, she observes how fragile relatives of starfish called brittlestars link arms to resist a strong current, then expresses gratitude to chronically ill friends “for the way in which we anchor ourselves to one another.”

Kenward: Sally is a naturalist, as well as a writer, and that practice and knowledge come through strongly. I am obsessed with the power of her metaphors. The piece is so skillfully and carefully crafted that it becomes a visceral experience to read. I'm particularly moved by her section on the octopus, which has been unceremoniously dumped on the shoreline. It’s surrounded by children, poked, then “rockets away, trailing dark ink.” She writes, “The octopus is the vulnerability of a sedated bodymind on an operating table. The ink is rage at the transgression of men who work in the medical profession.”

SEJournal: In the essay, “Things in Jars,” you write that you notice things “more acutely, more easily” when you move slowly, such as when you “emerge almost cocoon-like from another bout of illness or injury.” Isn’t the idea of slowing down something we can all relate to?

To slow down and shift our value

from productivity alone could

make a huge difference to us all.

Kenward: In a world that's constantly telling you to do things faster, more efficiently, it kind of goes against every cell in your body to stop and slow down. To learn to rest is absolutely something that would be beneficial for everyone. To slow down and shift our value from productivity alone could make a huge difference to us all. For me, it's about the pace at which I engage with the natural world. A lot of my writing has come from times when I haven't been able to get outside and do the kinds of things you might expect in a book about the natural world, walking or mountaineering or a kind of travel journal or field notes approach.

When I've been unwell, it makes more sense for me to connect with the changing of light during the day and the changing seasons, rather than the clock or the calendar, because all my body can do is basic functioning. Some days, it's the changing light that’s kept me engaged and connected with the world around me, and seeing that I'm surrounded by trees, or that different birds have different patterns for how they get through a basket of peanuts.

SEJournal: The book makes the point that these other voices and experiences are often excluded or invalidated. How does this exclusion and invalidation occur?

Kenward: It’s really tricky to navigate some of these complexities, because so much is embedded in how society operates, it can be difficult to see until you start looking. The barriers are multiple, subtle and persistent. Unless you have experienced marginalization of one kind or another, it can be assumed that “everyone is the same as I am,” whatever that might be — but the general regard for “normal” has been of a healthy white heterosexual cis man — certainly this has long been the case in medicine and medical research. And so that is what we are more likely to see. There are physical barriers for disabled people, like a lack of access to the natural world, a lack of accessible public transport that means you won’t see as many disabled people in the natural world as you might if there were equitable access.

Internalized ideas we carry

also perpetuate a societal

disbelief that ‘nature’ is relevant

or that we don’t belong outside.

Internalized ideas we carry also perpetuate a societal disbelief that “nature” is relevant or that we don’t belong outside. Similarly, barriers in publishing perpetuate societal stigma and stereotypes about what “nature writing” looks like and what gets published through editorial and commissioning choices. These are marginalized or minoritized groups marginalized at each stage of decision-making in publishing and society generally — and if disabled people are not in positions that commission or edit writing, then disabled people are less likely to be considered or represented as authors, or potential readers.

SEJournal: The contributors are primarily from the United Kingdom. But one, the American poet and writer Eli Clare, is from Vermont. How did you select them?

Kenward: Yes, I was reliant on my own networks, based in the U.K. I was also really pleased to include Cat Chong’s work, who had been living in Singapore, and Khairani Barokka, who grew up in Jakarta, Indonesia. I only commissioned authors who had already self-declared their disability or illness in the public domain. Eli is at the forefront of writing about the intersection of disability and gender in writing about the natural world. He wrote particularly powerfully about the fallacy of the “nature cure” and how problematic this is for disabled people. So he was a real “wishful-thinking” contributor I approached online, never thinking he’d accept. I am thrilled he did, and wrote such a wonderful piece that he was really wanting — and waiting — to write. I reference Eli’s work in the introduction, too. It has informed a great deal of my ongoing writing and research.

SEJournal: What advice do you have for environmental journalists and nature writers who don't live with disabilities or are not aware of these perspectives? How can we be on the lookout and try to tune in?

Kenward: It's the same as for any kind of marginalized community that isn't generally represented in the typical streams of media or journalism. The saying that comes from disability justice is, “Nothing about us without us.” If disabled editors and journalists are appointed, there will be more representation of disability in the writing commissioned and produced — although disabled people can write and commission work unrelated to disability, too!

An openness to engage with

different perspectives to those

typically considered will create

a richer knowledge and

understanding of the work.

There's something about being curious and keeping an engaging interest and awareness about disability and chronic illness. For journalists, editors and publishers to have an openness to engage with and a willingness to consider different perspectives to those typically considered will create a richer knowledge and understanding of the work they are doing — becoming allies of disabled people in doing so and more accurately representing the population — and widening their readership. Commissioning us to write about these themes and more is enormously important. For disabled people to be writing about topics nondisabled people do as well, to be just as representative as we are in society — so around 30% of all work published — would mean that there is a more equitable balance.

SEJournal: What's the story behind the title, “Moving Mountains”?

Kenward: It's one of those phrases used in common language referencing changing something that's huge and immovable. It’s pertinent to the necessity for change in regard and value of disabled people. But when I was in Canada visiting the prairies, I was struck by the endlessness and flatness of Saskatchewan, with very few trees. I loved it. And then to go to the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina, to see the timeline of the landscape and learn how it had long ago been mountainous, was wonderful. While we know the landscape has changed over millenia, to see it depicted on this timeline and to be in a place so well known for its flatness, was especially meaningful. It sat at the back of my head when I returned to the U.K. When I started the book, it came into my mind — that if mountains can literally wash and blow away, then maybe changing the landscape for people with disability and chronic illness is not impossible. It just takes time — time and persistence.

Louise Kenward, who lives outside Bexhill-on-Sea, in southeast England, is a writer, artist and psychologist, and a researcher at the Centre for Place Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University. She has been writer-in-residence with Sussex Wildlife Trust at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve. Her writing has appeared in Women on Nature, Elsewhere, The Bookseller, The Polyphony, The Clearing and the BBC Radio 3 series “A Landscape for Recovery."

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 11, No. 2. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.