SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

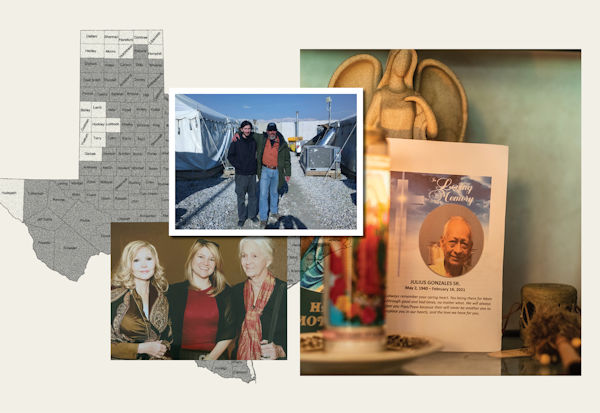

| BuzzFeed reported on officials’ neglect in preventing the Texas power grid’s collapse and concluded that the true number of deaths was likely four or five times higher than acknowledged. Image: BuzzFeed News; Courtesy the families. Click to enlarge. |

Feature: Reporters Reveal True Toll From Texas Winter Storm, Outages

By Peter Aldhous, Stephanie M. Lee and Zahra Hirji

When BuzzFeed News began investigating the number of people killed by the disastrous winter storm and power outages that devastated Texas in February, the state claimed that just 151 people had died as a result.

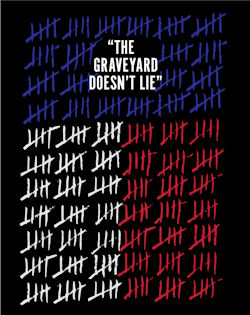

The grid failure had ravaged the state, trapping millions of people in freezing homes, often with no access to water. Our reporting for “The Graveyard Doesn’t Lie” exposed the full consequence of officials’ neglect in preventing the Texas power grid’s collapse despite repeated warnings of its vulnerability to cold weather.

In the end, our investigation concluded that the true number of deaths was likely four or five times the number acknowledged by the state so far. Our best estimate? Some 700 people were killed by the storm during the week with the worst power outages.

We wanted to give our investigation

an emotional gut punch that the

numbers alone could not provide.

To reach that conclusion, we relied on a statistical analysis of data on weekly deaths compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But we wanted to give our investigation an emotional gut punch that the numbers alone could not provide, and to offer more details about the conditions leading up to the victims’ deaths.

So we also used clues from that data, together with records of deaths we obtained from medical examiners’ offices in the largest Texas counties via public records requests, to find relatives of people who died during the storm. These family members provided harrowing accounts of their loved ones’ final hours.

Our story ultimately drew widespread coverage from local and national media outlets, and prompted state Democrats to demand an investigation.

‘Excess deaths’ analyses to the fore

Here’s how the project came about.

|

| BuzzFeed estimated some 700 people were killed by the storm during the week with the worst power outages. Image: John J. Custer for BuzzFeed News. Click to enlarge. |

Over Valentine’s Day weekend, Peter was tweeting about the unfolding disaster, realizing with alarm that millions of people had been left without power in freezing conditions. News stories revealed horrific tales of desperation as people burned their belongings to keep warm, watched their loved ones’ oxygen machines lose charge and inadvertently poisoned themselves with carbon monoxide by running generators, barbecue grills or their cars to combat the cold.

Given what he knew about the patchy recording of cause of death across the nation and in Texas in particular, Peter was fairly sure that the official death toll, compiled by the Texas Department of State Health Services, would miss many deaths caused by the freezing cold, instead attributing them to “natural causes.”

He was reminded of the staggering toll from Hurricane Maria in 2017. In that disaster, after news organizations, including BuzzFeed News, provided evidence that official deaths were being undercounted, The New York Times (may require subscription) and the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo compared deaths in earlier years to those recorded in the months after the storm made landfall.

While the official death toll for Hurricane Maria stood at just 64, these reports suggested that around 1,000 people had died in the prolonged power outages that followed the storm.

“Excess deaths” analyses like these have come to the fore again during the coronavirus pandemic, as academic researchers and news (may require subscription) organizations have tried to quantify the full death toll from COVID-19.

Meticulous statistical models

Peter started familiarizing himself with the CDC’s mortality data and the statistical methods involved. He built statistical models for each U.S. state, using the weekly deaths recorded from 2015 to 2019 to predict the expected number of non-COVID-19 weekly deaths through 2020 and 2021.

These models had two components: a linear trend to account for demographic changes and a seasonal trend to account for the variation within each year. For any week and state, Peter could then look at the difference between the actual number of deaths recorded and the predicted values, after subtracting recorded deaths from COVID-19.

Three independent academic experts

reviewed the analysis, agreeing that

there was a large spike in deaths in

Texas during the week of the storm.

Three independent academic experts reviewed his analysis, agreeing that there was a large spike in deaths in Texas during the week of the storm. (See here for full details of the analysis, written in the R statistical programming language.)

The mortality data compiled by the CDC lags by several weeks, as death records are slowly received from the states and processed. So Peter ran his code at regular intervals until he could see a clear signal linked to the winter storm. By the beginning of April, the numbers were still rising each time he ran the analysis code.

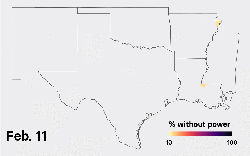

The analysis made clear that there was a large spike in deaths in Texas in the week of Feb. 14-20. Notably, similar spikes didn’t show up in neighboring states that were affected by the winter storm, but that didn’t experience such severe and prolonged power outages.

Gathering lists of deaths

That triggered the next phase of the reporting: Peter filed public records requests to medical examiners’ offices in eight of the largest counties in Texas, asking for lists of all deaths recorded in that week, including name, age, address and cause of death.

He also looked at what the CDC data recorded as the specific causes of deaths in Texas in the week of the power outages, finding that the biggest spikes were for deaths attributed to cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Peter then highlighted deaths from these conditions in the records from the state medical examiners so that Stephanie and Zahra could approach relatives of people whose deaths may have been linked to the storm.

That prompted him to read the scientific literature and speak with medical experts. He learned how freezing temperatures can exacerbate underlying medical conditions like cardiovascular disease and that deaths from hypothermia are often mistakenly attributed to underlying medical conditions.

Reaching out to relatives

Once Peter had gathered the names of people who had passed away during that terrible week, Zahra and Stephanie set out to contact their relatives. In non-COVID-19 times, we might have flown to Texas, driven around and knocked on doors. Instead, we set out to find family members over the internet and phone.

|

| Click to view an animated image showing the percentage of customers without power across the region by county before, during and after the storm hit. Image: Peter Aldhous of BuzzFeed News, via poweroutage.us. |

A few strategies made the search easier. Stephanie would first plug the deceased’s name into Google and search for an obituary. These typically contained basic biographical information (age, location) that helped confirm that they were the same people in our death records.

Not everyone, sadly, appeared to have an obituary. So if one had run at all, she interpreted that as a sign that relatives — whose names were usually listed — might be open to talking about their loved ones. Stephanie also searched Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram and GoFundMe pages.

She looked up names and numbers through public information databases that our newsroom subscribes to, such as LexisNexis and TLO. But, as any reporter who has used these knows all too well, most of the numbers were disconnected or wrong.

By Stephanie’s count, she put out more than 300 calls and emails, successfully reaching the relatives of about a dozen people who died during the week of the storm. Zahra had similar luck. A handful of the families we spoke to ended up in the story.

Harrowing conversations

These conversations, for which Stephanie is deeply grateful, were often harrowing. She always started by saying that she was sorry for the family’s loss and to be calling out of the blue. She explained what we were curious about: We had reason to believe that the storm’s death count was higher than the official count, and did they think that the storm had something to do with their loved one’s death?

Many family members spoke

out of a sense of anger that

their loved ones were left to die.

Many family members spoke out of a sense of anger that their loved ones were left to die. But Stephanie sought to avoid forcing a connection (and a few people didn’t think the storm played a role, or weren’t sure).

With those who did think the storm was a factor, she interviewed them several times to gather details relevant to the big-picture trends Peter was seeing in the data and his interviews with experts. What was their relative’s medical condition before the storm? Did their homes have access to heat and water? What were they saying, wearing, doing in their final hours?

Once we collected their stories, we asked the medical examiners in their counties why these fatalities hadn’t been counted as storm-related. This helped shed more light on the holes in the data: One examiner told her that some families had never disclosed that their loved ones were cold before they died. Those families, in turn, told Stephanie that no one had ever asked them.

Reporting the grid collapse

As the winter storm was unfolding last February, Zahra was the primary BuzzFeed News reporter covering the widespread blackouts. The state’s key power infrastructure, such as natural gas wells and pipelines, was ill-prepared for cold weather and froze up, cutting off electricity to millions.

Zahra reported on how the grid collapse was “seconds and minutes” away from being even worse and how the state was warned a decade ago about the grid’s vulnerability to the cold. Her contribution to this investigation involved detailing what happened to the power grid during the storm and then the ways Texans sought accountability afterwards.

She reconnected with the energy experts from her initial Texas reporting and with local environmental activists. All of them pointed to a bill called SB3, which would give state regulators the authority to require power providers to harden their equipment against cold temperatures or face fines. But her sources agreed that even if it did pass, it would not go far enough in addressing all the systemic problems identified during the storm.

Then Zahra decided to check the courts. Using a tool available through LexisNexis called CourtLink, she searched for wrongful death lawsuits filed across Texas against the state’s grid operator, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT. She found more than 30 cases, creating a spreadsheet to keep track.

Initial lawsuits just the tip of the iceberg

Some patterns quickly emerged. First, the stories of how people died were eerily similar, often involving older people, sometimes alone, who did not have heat for hours to days before their deaths. Second, the same law firms appeared over and over.

Zahra reached out to those firms, and the lawyers explained the lawsuits she had found were just the tip of the iceberg — dozens more families had yet to file.

For some of the families suing, the official cause of their relative’s death was listed as storm-related. But this wasn’t the case for most of those who died that week. The lawyers said their clients’ experiences suggested many more people likely died in the storm than the official numbers admitted, matching the takeaway of our analysis into the number of uncounted deaths across the state.

Many Democrats called for the state to

lead an investigation into the true

number of fatalities as a result of the storm.

Days after our story published, Zahra led our efforts to seek comment from legislators in Texas. None of the Republicans contacted by BuzzFeed News responded, but many Democrats called for the state to lead an investigation into the true number of fatalities as a result of the storm.

“The loss of life that is depicted in this story is heartbreaking and the fact that the death toll numbers have been miscalculated is absolutely unacceptable,” said Rep. Marc Veasey, a member of the House’s Energy and Commerce Committee. “We can’t let this stand. We need answers and accountability.”

That weekend, as expected, SB3 passed through the state legislature, but it will still take years for its many proposals to take effect. In the meantime, the summer’s hot weather is already wreaking havoc with the state’s power grid.

|

Peter Aldhous, at right, is a science and data reporter at BuzzFeed News, based in San Francisco. Before that he worked as a reporter and editor for Nature, Science and New Scientist.

Aldhous teaches investigative journalism in the Science Communication program of the University of California, Santa Cruz and data visualization at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley and the Berkeley Advanced Media Institute.

|

Stephanie M. Lee, at left, is a reporter at BuzzFeed News, where she covers science, health and medicine with a focus on accountability. Before joining in 2015, she was a staff writer at the San Francisco Chronicle.

Lee's work has been anthologized in The Best American Food Writing. She graduated from the University of California, Berkeley and lives in San Francisco.

|

Zahra Hirji, at right, is a climate reporter at BuzzFeed News, based in Washington, D.C. While on staff, she was a 2018 Ida B. Wells Fellow with Type Investigations.

Hirji previously reported for Inside Climate News, Discovery News and Earth Magazine, and received a Masters in Science Writing from MIT.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 27. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement