SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf: A Look Back at the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement

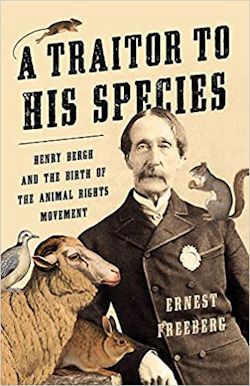

“A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement”

By Ernest Freeberg

Basic Books, $30.00

Reviewed by Jennifer Weeks

|

The struggle against slavery was the defining moral quest of the 19th century in the United States, but it wasn’t the only crusade.

Early in 1866, Henry Bergh, a wealthy New Yorker in his 50s, founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, or ASPCA, and launched the struggle to protect animal welfare.

In this eye-opening account by University of Tennessee historian Ernest Freeberg, the author recounts how Bergh framed the issue for a public that was used to thinking of animals as dumb creatures placed on Earth for human use, and so launched a movement that has only gained strength over the decades since his death in 1888.

In many ways, Bergh anticipated the media age tactics used now by more radical organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

A focus on horses

Bergh explained his midlife conversion story thus: While working at a diplomatic post in Russia in the early 1860s, he saw carriage drivers brutally mistreating horses in the streets.

Seeing a man whipping his horse, Bergh intervened and ordered him to stop. When the man dropped his whip, Bergh believed he had found a positive way to use the power and status to which he had been born.

Horses were a major focus of Bergh’s activism once he returned to New York. In post-Civil War America, horses powered everything — farming, commerce, public transportation — and often worked until they literally dropped dead in the streets.

In 1867, Bergh secured passage of a sweeping statute by the New York legislature that greatly expanded existing animal cruelty laws.

The statute forbade overdriving, overloading, torturing, tormenting, depriving of necessary sustenance, unnecessarily or cruelly beating, or needlessly mutilating or killing any living species — not just animals of commercial value. It also barred animal fighting, such as bull-bear, dog and cock fights.

Most notably, the law empowered ASPCA agents to arrest violators on the streets.

Taking on New York City, celebrities

Bergh became a familiar presence in New York City, stopping overloaded trolleys, lecturing the drivers on animal cruelty and morality, and dragging resisters to court.

Bergh also accompanied police on raids of notorious spots such as Sportsmen’s Hall, a dog-fighting arena in lower Manhattan.

He made it a mission to drive unscrupulous operators out of business and to publicize the carnage that took place in backroom operations.

Like activists today, Bergh

understood the value of

taking on famous people.

Like activists today, Bergh understood the value of taking on famous people.

His targets included circus operator P.T. Barnum and wealthy magnates such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, who owned urban horse-drawn trolley lines (the “last miles” of their railroad empires).

Bergh tried to have railroad barons prosecuted in court for running overloaded railroad cars with sick horses, but was rebuffed by judges who asserted the only men responsible were drivers caught in the act.

Advocates echoed work in other cities

This book is also a lively trip to U.S. cities in the 1860s and 1870s, when American society ran on horsepower, with steam looming on the horizon. And Freeberg describes how Bergh’s efforts were echoed by advocates in Boston, Philadelphia and other cities.

Some activists, particularly women, focused on educating children about treating animals humanely, believing that creating a generation of kind young Americans was ultimately the way to defeat the problem.

Back then, livestock was shipped to U.S. cities for slaughter — a practice that appalled Bergh. Although he was no vegetarian, Bergh feared that if Americans became accustomed to seeing pigs, sheep and cows driven through the streets to stockyards (often weakened after harrowing journeys from the farm), they would become indifferent to animal suffering and death.

Activists nationwide lobbied for laws requiring better treatment of animals on their journey to market, and Bergh publicized cruel and disgusting conditions in New York slaughterhouses.

Their arguments helped spur companies such Swift and Armour to centralize the meat processing industry in the Midwest, which ultimately put it out of sight and out of mind for most Americans.

Animals as companions?

In the decades when Bergh was active, most Americans knew little about animals. When Bergh pressed a case in 1866 against a ship’s crew for cruelly mistreating sea turtles they were carrying north to New York restaurants, headlines asked, “Is a Turtle an Animal or a Fish?”

Stray dogs and cats were nuisances, not creatures that deserved sympathy and care.

But the United States was becoming an urban nation, and many Americans were increasingly open to the view that animals could be companions and friends, not just useful commodities.

Bergh did much to advance that idea, often using public relations and media tactics that wouldn’t be out of place today.

This illuminating book — with copious reference to contemporary media accounts — shows how far the United States has come on an issue that we still struggle with today.

Jennifer Weeks is senior environment and energy editor at The Conversation US and a former board member of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 28. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.