SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

BookShelf: Solutions — and Death — in the Rainforest

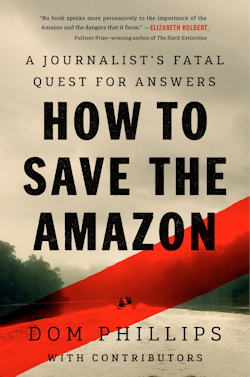

“How to Save the Amazon: A Journalist’s Fatal Quest for Answers”

By Dom Phillips and contributors

Chelsea Green Publishing, $27.95

Reviewed by Elyse Hauser

“How to Save the Amazon” begins with a venomous snake.

|

British journalist Dom Phillips is deep in the rainforest, with a group of Indigenous men and boys. To Phillips’ eyes, his Indigenous companions (even the children) seem casual, if not downright gleeful, while killing snakes from the undergrowth.

But Phillips’ fear of the deadly reptiles is tangible. He could not know, as he drafted these opening lines, that he would meet his demise from a deadly Amazon threat not long afterward. Not a snake, this time, but a person with a gun.

Phillips was halfway through writing this book when he was murdered during a river trip. Murdered alongside him was Bruno Pereira, the Brazilian Indigenous specialist who’d become a guide and partner to Phillips.

Amazon murders are common: illegal activity from mining to drug trafficking is rampant, and people in those illicit businesses often kill to protect their interests.

Yet these murders rarely reverberate worldwide. Phillips’ and Pereira’s did, largely because Phillips was a white British journalist with a broad international network.

Finished posthumously by that network, “How to Save the Amazon” became a very different book. It still sticks to Phillip’s goal of highlighting solutions that might protect the rainforest. Yet it also became a metaproject, examining the value, and the risks, of foreign journalism in a delicate ecosystem.

Phillips came from the white, European, capitalist realm that has driven environmental destruction across much of the globe, including in the Amazon. Could his attention — and the global attention that followed his death — assist in its protection?

Dense with background

Phillips gives readers a few welcome glimpses of the Amazon he’d come to love. His first chapter ventures to the Javari Valley, a remote Indigenous territory of treacherous beauty. He shows us the towering mahogany tree, the rust-colored honeycomb.

Yet after this opening chapter, he spends less time writing about the rainforest itself. The next few chapters are dense not with undergrowth, but with background. Phillips meticulously covers the Brazilian politics and laws that allow, and even encourage, deforestation.

This regulatory world makes cattle ranching on illegally cleared rainforest a safe and profitable venture. The loopholes are dizzying. To Phillips, Brazil’s Amazon policies seem “schizophrenic.” He details these policies at a breakneck pace, all while adding history and long lists of political names.

Some shocking details

stand out, such as the

sheer speed of deforestation.

It can be hard to keep up. Still, some shocking details stand out, such as the sheer speed of deforestation. Less than 1% of the Amazon had been deforested by 1975. Now, driven largely by cattle ranching and monocultural farming, 20% has been clear-cut.

Visiting a ranch, Phillips notices an overgrown pasture, where the grass is twice his height, the trees leg-thick. Reforestation is possible, though it won’t be quite the same. Yet the rancher is clearing out most of this new growth on his land. It’s not profitable to let the forest grow back, he tells Phillips.

‘And then, he became the victim’

It is these vivid, visual moments in which the destruction feels so palpable, the crisis so extreme. Yet Phillips’ pauses to really show us the landscape remain few and far between.

He spends many more paragraphs laying out destructive policies and possible solutions. Those solutions range widely, from agroforestry to mutual aid. Such sustainable and supportive practices can strengthen the rainforest’s defenders, while ensuring all the locals have what they need.

As he recounts these

travels, his endearing

nervousness emerges.

Phillips ventured across Brazil to find these forest-saving ideas. As he recounts these travels, his endearing nervousness emerges. He fears helmetless motorbike travel, snakes, caimans, poisonous frogs and the risk of choking while eating fish.

Yet he never seems to fear other people in the Amazon. Even when he stumbles upon a murder as it’s happening, the momentary fright doesn’t translate into a general mistrust of the people he encounters.

And then, he became the victim. An image of two crosses — one for Phillips and one for Pereira — marks the end of the chapters that Phillips was able to finish.

Emotional essays by friends and colleagues

Yet this is not the end of the book. His journalist friends pulled together to complete the second half, based on the rough notes and chapter outlines they were left with.

These sections offer welcome context, not just about the rainforest, but about the author himself. Phillips’ love for the Amazon was only a few years old, his co-authors note. His ideas were still developing.

By later chapters, his notes called for listening to Indigenous people, even those with radical ideas about reshaping how the world works. But we’ll never know how his developing sense of “how to save the Amazon” might have influenced his earlier chapters, and indeed the whole text, had he had a chance to finish it.

Instead, the book moves from Phillips’ dense account of history, politics and problem-solvers into a more vivid series of emotional essays by his friends and colleagues. These authors got to edit their work; their sections read more easily, with polish. Still, the subject matter is unwieldy.

The Amazon faces an entangled mess of threats. There are no easy answers, no proven solutions. Each chapter focuses on a possible fix. Sustainable harvests of fruit, fish and medicine might help. So might offering cash incentives to preserve more forest.

These chapters can inspire readers to think more deeply about what makes an effective solution. But “How to Save the Amazon” cannot tell us how to save the Amazon, because that would require a level of coordination and investment almost too large to imagine.

The book’s very existence

is a testament to collaboration

in the face of crisis: a small

reason for hope in itself.

So far, there’s no countrywide (much less worldwide) support for implementing these ideas at an effective scale. At the same time, the book’s very existence is a testament to collaboration in the face of crisis: a small reason for hope in itself.

A later chapter suggests that no one can truly sense what’s at stake unless they experience the incredible power of the Amazon. Yet because it never lingers long in the rainforest, “How to Save the Amazon” doesn’t give readers a sense of that power.

Instead, this book shows the power of people: contradictory and convoluted, destructive yet determined. Readers may long for more time in the Amazon that Phillips loved so much: its scents, its sights, its sounds.

Getting the information behind the destruction — history and politics, regulations or lack thereof — is important, as is peering into possible solutions. But it would’ve also been valuable to pause in this fast-moving modern story and reflect on the raw, ancient physicality of the Amazon, on what’s being lost.

It’s easy to imagine that had Phillips lived to finish his book, he would have done just that.

Elyse Hauser is a freelance writer from the Seattle area who specializes in environmental writing. In 2023, she was named a co-editor of SEJournal’s Freelance Files column. This is her first contribution to BookShelf.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 10, No. 26. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.