SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

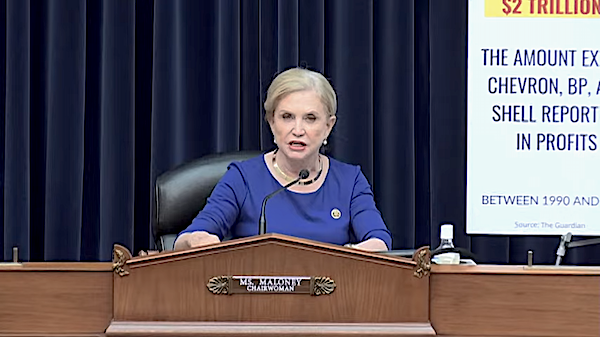

| Companies are required by the U.S. government to report very little, and the ways corporations measure progress are mostly not standardized. Above, a screenshot of House Oversight Committee Chair Carolyn Maloney at 2021 hearings that led to a report on greenwashing efforts from Big Oil. Image: Committee on Oversight and Reform via YouTube video. |

Climate Solutions: Measuring the Impact of Corporate Commitments

By Megan Myscofski

Corporations have felt a new kind of pressure for the last few decades, beyond the normal push for innovation and sustained growth. More consumers, investors, government agencies and even employees want companies to demonstrate values that align with their own. And as climate change accelerates with significant contributions from some of these corporations, many of those constituencies are asking them to invest in solutions.

|

As a result, it has become more common to see CEOs speak out on social issues and weigh in on politics in ways that most would have avoided in even the recent past. Corporations also make commitments to mitigate their impacts on the environment and share data that reflects changes they make to this end.

Some of this work can have a meaningful impact, some is just smoke and mirrors, and plenty of it falls somewhere in between.

“It’s so hard to know how to cover these announcements because there’s so many of them,” POLITICO Deputy Sustainability Editor Debra Kahn said in a recent Society of Environmental Journalists webinar on covering corporate climate solutions. “There’s so many acronyms and groups bouncing around, and there’s so little enforcement and framework to actually account for, you know, ‘Do these things mean anything?’”

It’s always worth remembering that

companies are driven by profit.

That’s why many say regulation is key.

When you’re reporting on corporations, it’s always worth remembering that companies are driven by profit. Even when they speak out on an issue or launch a new program, they have targets to hit and need to prove they’re growing to shareholders who will hold them accountable to that.

That’s why many government officials, researchers and activists who work in this space say regulation is key. Companies aren’t set up to prioritize a community’s needs, but governments are, at least in theory.

And although there’s been more pressure than ever on companies in the last couple of decades, there’s still more oil production, carbon emissions, environmental damage and social inequity.

Reporting standards uneven, regulation limited

Companies are required by the U.S. government to report very little, and the ways corporations measure progress are mostly not standardized.

About 90% of the world’s largest companies do produce a corporate social responsibility report. However, there is no set way to draw these up — each company decides what information to include, and it varies widely.

But there are standards that a company can choose to employ. The Global Reporting Initiative, for instance, is an independent organization with roots in the United Nations Environment Programme that sets standards for companies to use. Even when using outside standards, however, very few companies enlist a third party to validate their reports.

It can also be difficult to find and quantify the kind of information that would present a clear picture of a company’s environmental impact.

For a company to give a full assessment of its carbon footprint, for example, it would need to meet multiple tiers of criteria: the emissions it directly produces in its own facilities, emissions that come from the electricity it uses, what its suppliers and distributors contribute, and by usage of its products. Fewer than half of the companies that choose to report a carbon footprint cover all of these aspects.

Supply chains alone come with many hurdles to transparency, as they can be very difficult to trace. Many products incorporate parts and labor that span the globe. What’s more, many companies produce goods in countries where regulations are laxer and a chain of contractors and subcontractors can easily leave room for companies to sidestep culpability. That can make the production of a given good so opaque that even an audit can’t fully prove everything is above board.

On top of that, a company’s carbon footprint won’t give you a complete view of its impact in this area.

“There are so many other things happening on other sides of the company that often completely eclipse what their actual emissions are,” Jamie Beck Alexander, director of Drawdown Labs and Project Drawdown, said in the SEJ webinar. She recommended that journalists look into a company’s finance submissions, banking practices, insurance, governance practices and lobbying to get a more complete picture of a company’s progress towards sustainability measures.

- Solutions to explore: More federal regulation could be on the horizon. The House Committee on Oversight and Reform released a report in December 2022 on greenwashing efforts from Big Oil. That documentation could help bolster lawmakers’ arguments for stronger regulations and oversight. Any push for more regulations could include more standardization in the way these efforts and outcomes are measured. On a local level, reporters can look into a company’s impact on their community, whether it be political donations, contact with local officials or other aspects of a business beyond direct emissions, and see how it measures up against the more general stances the company takes.

Uncertain degree of government influence on sustainable practices

Governments can also throw their weight behind sustainable business practices through subsidies. Looking into what subsidies or tax breaks a federal or state government issues can reveal a lot about its priorities, as well as the progress officials have made on campaign promises.

For example, the Environmental and Energy Study Institute reported in 2021 that the United States issues about $15 billion per year in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, while states provide about $6 billion. These subsidies were instrumental in the shale boom, which increased fracking. That doubled crude oil production and made the United States a net exporter and the world’s largest producer in just a decade.

- Solutions to explore: This is where talk of “green jobs,” the “Green New Deal” and “clean jobs” comes into play. Some lawmakers have pushed for federal funding to move away from industries like oil and gas and towards solar, electric vehicles, etc., to mitigate climate change. President Biden’s Build Back Better plan was meant to put some of these ideas in motion, but ultimately wasn’t passed. The pared-back Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, or IIJA, which does contain some of these policies, did make it through Congress in 2021. But as the Center for Strategic and International Studies wrote in a 2021 report, “Biden’s core climate commitments, a 50-52 percent reduction in greenhouse gases (GHGs) by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050, cannot be reached with business as usual — they require bold action. But the IIJA contains more of the former than the latter.” Still, the IIJA is putting unprecedented funding behind infrastructure projects, including money to grow these industries at a faster clip. There will be a wealth to report on in the coming years regarding the use of these funds. I would encourage reporters, especially at the local level, to look into what funds their state and local governments are applying for, and who is responsible for the paperwork. I’ve reported in the past on the extensive work this takes, which leaves many communities out if they don’t have the staff or know-how to access it. There will also be states and municipalities that outright leave money on the table for these projects.

Ethical investing standards tough to assess

Environmental, Social and Governance, or ESG, investing is billed as a way for investors to support companies that share their values, from environmental sustainability to equitable treatment in the workplace.

ESG funds are made up of stocks and bonds chosen based on a set of social criteria. For example, an ESG fund that emphasizes environmental sustainability will, in theory, feature investments in companies that show a commitment to good environmental practices.

There’s no one set of standards to

evaluate ESG funds. That means it’s

hard to compare these funds between

investment managers or assess them.

There’s no one set of standards to evaluate ESG funds. Investment managers that run such funds will each have their own criteria for how they judge them. BlackRock, for example, assigns its ESG funds a number of sustainability scores, such as a measurement of the fund’s weighted carbon footprint.

That means it’s hard to compare these funds between investment managers or assess them. As you can imagine, environmentalists and experts in this field are split on how much impact ESG investing can realistically have.

Barclays released a report saying there is virtually no difference in impact between ESG funds and others, and a Wall Street Journal investigation (subscription required) from 2019 showed that eight of 10 of the biggest U.S. sustainable funds were invested in oil and gas companies.

Some Republican lawmakers, such as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, have spoken out about ESG investing, calling it “corporate wokeism,” and have made moves to block it. The states of Florida and Louisiana both pledged to pull investments (subscription required) from BlackRock in 2022 because the firm engages in ESG investing.

- Solutions to explore: ESG investing is still relatively new and developing. Many who see it as a useful tool argue that more transparent and standardized metrics for ESG funds would increase their impact. For local journalists reporting on pushback by local leaders, it might be worth looking into your state’s investments, and especially its pension fund, to see who’s managing it, and where it’s ultimately going.

Carbon offsets, net-zero targets may not truly limit emissions

Carbon offsets are credits that one can buy to compensate for emissions. The resulting funds go toward projects that lower CO2 emissions, or that take them out of the atmosphere and store them. Companies will buy credits to make up for their CO2 emissions rather than lower their own. That means it’s possible for a company to bring down emissions to “net-zero” without getting them to “zero.”

The best-known example of carbon offsets are programs that plant trees in order to take advantage of a forest’s ability to soak up carbon that would otherwise stay in the atmosphere. Others might retrofit low-income housing for energy efficiency or fund research for sustainable technology or agricultural practices.

Some critics say that while offsets can have a positive impact if a company has done all it can to lower emissions, many companies use them as a way to signal that they’re working towards improving the environment without changing their own operations. It’s also very difficult to measure emissions reduced, especially as in order to be effective, projects funded by carbon offsets must reduce emissions that wouldn’t have otherwise been reduced and that have longevity in the atmosphere.

“Many of the pledges say they’re net-zero, but in truth, the pledge itself is not accounting for the majority of emissions in different ways,” Raya Salter, founder of Energy Justice Law and Policy Center, said of pledges from big oil and fossil fuel companies in the SEJ webinar.

And though it’s slowly changing, companies also tend to leave consideration of environmental goals until late in a product’s development.

- Solutions to explore: When a company announces new goals or efforts, see if it can show the math. If the company is meaningfully bringing down emissions across its operations — considering the impact of its products from the development stage on and choosing to work with companies and organizations that do the same — its efforts to support climate resilience in the above ways will have a greater overall impact.

[Editor’s Note: For more resources on business-based solutions, as part of the Covering Climate Solutions special report, see our toolbox on corporations and climate change.]

Megan Myscofski is an environmental reporter at the Albuquerque Journal. She previously worked as a business and economics reporter at Arizona Public Media in Tucson, where she reported, produced and hosted a podcast on the economic side of water issues called Tapped. Myscofski also formerly worked at Montana Public Radio as a reporter and Morning Edition host, and received a master's degree from the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. Her work has run on NPR, Marketplace and KUNC, among other outlets.

Advertisement

Advertisement