SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

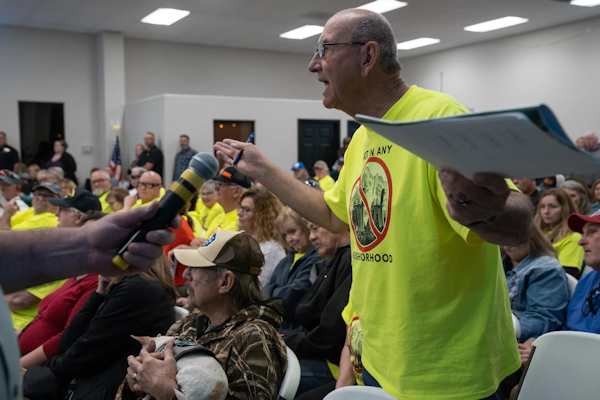

| Sunrise Hills resident Bob Hooker speaks at Feb. 12, 2024, Mohave Energy Park Town Hall. Photo: Courtesy Mark Henle/Arizona Republic. |

FEJ StoryLog: Battle Over Gas Power Facility Generates Months-Long Investigation

By Joan Meiners

At the beginning of January 2024, a group of retirees living in the Sunrise Hills community in rural Arizona messaged me, the climate reporter at The Arizona Republic, seeking help in their fight against a natural gas peaker plant approved for construction near their homes.

This vast desert region outside of Las Vegas is among the best in the country for solar energy potential, with a few modest arrays owned by local utilities already in place.

It seemed the more residents

voiced their opposition to the new

gas plant, the more the utility company

doubled down on its necessity.

Yet as I started to research the issue, I learned that Mohave County supervisors had recently voted to ban new solar projects. Six weeks after that, they had quietly approved zoning for a new gas plant instead, bypassing the requirement for a new application by extending a zoning designation for another unbuilt facility that had previously expired. And, it seemed, the more residents voiced their opposition to the new gas plant, the more the utility doubled down on its necessity, using disinformation scare tactics, like billboards suggesting local hospitals would fail without it.

I was intrigued by this dynamic. Here was a community of older, white, middle-class Arizonans, most of whom proudly identify as Republican, who had become defacto climate activists in their desire to prevent pollution near their homes — while a utility company in a state without notable natural gas reserves seemed to be refusing to capitalize on the cleanest, cheapest, most available source of energy available to them: the sun.

Initial reporting led to a road trip

After several phone conversations with the Fort Mohave residents, I drove four hours from Phoenix in early February to meet with the group. We gathered in one of their giant boat garages, where they made their case against the gas facility slated for less than half a mile from their homes, just beyond the backyard of one senior couple in the neighborhood.

It would be an eyesore, they said. It would reduce property values. The gas could present an explosive safety hazard. It might be noisy. And most of all, it would pollute the air some residents with preexisting respiratory issues had specifically moved there to enjoy.

I joined them at a community meeting hosted by the two utility companies partnering on the $85 million gas project: the Mohave Electric Cooperative and the Arizona Electric Power Cooperative. Both were 501(c)12 not-for-profits and claimed this meant they had no other motive to build a gas facility other than pursuing the best portfolio of diversified energy resources for their customers.

The community, many of whose

homes would not even be served

by this facility or providers,

was not buying it.

But the community, many of whose homes would not even be served by this facility or providers, was not buying it. The meeting got heated. At one point, Arizona Republic photographer Mark Henle whispered to me that he wondered if a fight would break out.

No physical altercations took place that night. But the bitter fight over the facility stretched on for months. I stayed in touch with residents while I dug into details about the project. I filed public records requests asking for permitting documents and copies of emails between residents, utility executives and local politicians. And I interviewed dozens of experts about what was normal in terms of solar reliability, western grid functionality and operations at 501(c)12 not-for-profits.

First story caught state attorney general’s attention

The first story in this investigation ran in early April 2024. In a narrative format, I outlined the residents’ concerns, the evidence that the zoning process went against county protocols and opinions from many energy experts that there was no clear reason why this utility could not increase its generation capacity with solar and battery additions instead of gas.

We saw immediate impact. The Arizona Attorney General opened an investigation into the zoning process and the gas plant project, and reached out to my quoted sources for comment. Residents brought hard copies of my story to county supervisor meetings and held them up during public comment, asking their elected representatives to educate themselves on my reporting. And a few days after we published, the utility company announced that they would look for an alternative site for the gas project.

This was encouraging progress

and a testament to the power

of community activism and

journalism combined.

This was encouraging progress and a testament to the power of community activism and journalism combined. But I still had questions about why these utility executives were doubling down on a gas plant when everyone I spoke with said that, with careful management, the electricity needs could be met cheaply and reliably with cleaner solar and battery storage — resolving the residents’ concerns and the entire debate.

So I set to work on a second story to delve deeper into potential financial or political motives for a gas peaker plant and to find out what was going on between utility executives and county supervisors that might have led to a local ban on solar projects, from which only local utilities were exempt (meaning this on its own did not explain their push for a gas plant).

Late on a Friday afternoon, I received a response to my records request from Mohave County — a 715-page document of emails, including some between then-Supervisor Hildy Angius and the leadership team at the Mohave Electric Cooperative. I couldn’t resist skimming the full document at once.

Records request, more reporting yields answers

In snide, familiar emails between Angius and utility leaders, the elected official complained about her constituents’ requests for information about the gas peaker plant and its risks, and that she visit the site to see how close it was to their homes.

In one email singling out the most active neighborhood activist, MEC’s Chief Operating Officer Jon Martell wrote to Angius that, “I feel like he is setting us both up.” She replied minutes later that the situation was “too political” and she was “getting pissed off.”

I also uncovered a letter of support for the gas project addressed to state utility regulators, urging them to approve it. It had supposedly been authored by Angius, but email records revealed it had been sent to her for her signature by MEC CEO Tyler Carlson.

These interactions confirmed my hunch that those in power promoting this gas plant were not doing so with open minds and respect for the interests of local customers, but were instead engaged in some other pursuit. Angius was running for a state senate seat (which she later won), and was perhaps hoping to keep cozy relationships with local industry reps. And, as I learned by poring over MEC’s not-for-profit tax documents, Carlson stood to gain a lot personally from successfully pushing this gas plant through.

By reviewing 990 tax filings, I had discovered that, in 2017, Carlson was paid $1.7 million. His salary then dropped by more than 60% in 2018 to just over $600,000 before surging back up to $1.2 million in 2020. It decreased again to $650,000 in 2021, and then more than doubled in 2022 back up to $1.4 million.

An expert in not-for-profits at Arizona State University confirmed for me that this dramatic fluctuation was highly unusual and hard to explain. He speculated that it may depend on Carlson’s performance securing profitable projects in rural communities. MEC’s CEO did not respond to my questions about this.

But a call with AEPCO’s CEO, Patrick Ledger, confirmed that this was how bonuses at these utilities often work. I then verified with solar energy and western grid experts that building a gas plant in this well-connected part of Arizona, situated at a major hub of western transmission lines, would indeed generate more revenue than solar for this not-for-profit utility, because gas would allow them to pump electricity onto the grid for sale across the West at all times of day.

At last the pieces all came together, and then a result

The Republic published the second story detailing these investigative findings in June 2024, couched in a narrative about new community conflicts emerging in Mohave Valley — MEC’s proposed alternative site for the gas project.

It’s impossible to avoid small-town drama when covering rural controversies like this, which can be intense! For this second story, I attended another community meeting in May where the local fire chief shouted across the room at another resident while members of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe tried to voice their concerns. The next morning, I went fishing with a tribal member to talk about the importance of clean energy and land stewardship. Showing up in person and reflecting residents’ real lives and concerns in the reporting helps build trust and understanding.

Over the next six months, I checked in with my sources regularly amid ongoing conflict and as a county meeting to review the zoning approval, which had been questioned by the state attorney general after my first story ran, was pushed back and rescheduled multiple times.

Then, on Dec. 23, 2024, Mohave County Supervisors finally rescinded their approval for the gas plant at its originally proposed location. I celebrated Christmas Eve on the phone with some of the residents who had first contacted me in early January, as we discussed their victory and the power of both local activism and accountability journalism. A third story, about the vote reversing approval of the plant, ran a few days later.

The Arizona Republic is a local newspaper with limited travel funding. I’m not sure if any of this would have been possible in such depth without the grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists' Fund for Environmental Journalism. I’m pleased to help showcase the type of reporting and outcomes this funding supports.

Joan Meiners has been the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com since early 2022. Her award-winning work has also appeared in Discover Magazine, National Geographic, ProPublica and the Washington Post Magazine. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in ecology with a focus on the biodiversity of native bees. Follow Joan on X at @beecycles, on Bluesky at @joanmeiners.bsky.social or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 10, No. 23. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement