SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

| Squeezed between the Pacific Ocean and Cascade Range in Washington lie green forests and rolling farmland. But the region is facing warming temperatures with potentially profound effects. Above, the view north from Crown Point, Wash. Photo: Don Graham, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Covering Your Climate: The Emerald Corridor — Impacts, fixes and rethinking everything

This Society of Environmental Journalists’ special report — “Covering Your Climate: The Emerald Corridor” — is meant to help journalists in the Pacific Northwest cover the impacts of climate change, as well as action taken to mitigate its worst effects and adapt to what can’t be stopped.

Not on the environment beat? This special report is also meant for you. That’s because climate change touches everything, whether obvious or not: the economy, energy, science, government and politics, weather, nature, food, water, physical and mental health, technology, transportation, education, recreation, lifestyle, international politics, population growth, real estate, zoning, insurance and national security.

“Covering Your Climate: The Emerald Corridor” begins with the backgrounder below. In the coming weeks, we’ll also publish a toolbox of sources and three tipsheets with a wealth of story ideas for right now, and over the coming decade.

The project is distributed through SEJournal and the journalism nonprofit InvestigateWest.

|

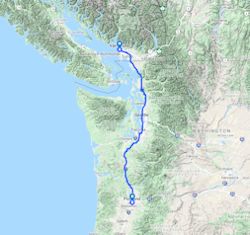

| The Emerald Corridor runs from Vancouver, B.C., through Washington, then south to the Willamette Valley surrounding Portland. Image: Google Maps. Click to enlarge. |

By Christy George

There is one phrase that’s been used to assess the impacts of climate change by all the governments of British Columbia, Washington and Oregon: “historically unprecedented.”

All three places have green reputations and are viewed as climate leaders. How green are they? How will leaders in government, business, religion and other institutions respond? How will people cope? How will these places change? Those are the stories that journalists of all stripes will confront.

This project focuses on the so-called “Emerald Corridor” that runs from Vancouver, B.C., through Washington, then south to the fertile Willamette Valley that surrounds Portland. The region is squeezed between the Pacific Ocean on the west and the snow-capped Cascade Range to the east. In between lies a lush strip of green forests and farmland with reliably rich soils created by volcanic eruptions, watered regularly with rains and irrigated by melting snow.

Until now.

As the climate has warmed, so has the Emerald Corridor, by a total of 1.5 to 2 degrees Fahrenheit. It may not sound like much, but the effects can be profound.

What’s coming at us

All three governments, state and provincial, list the same three top problems: rising temperatures, severe wildfires and heatwaves, all of which bring health problems, as well as loss of life and property. Their leaders all also worry that there could be simultaneous or cascading climate-driven events

One of the hallmarks of climate change is variability, and what happens to water is key.

|

| Severe wildfires are among the region’s biggest worries, with long-lasting droughts weakening trees and making forests more fire-prone. Photo: Jeremy Bochart/Bureau of Land Management Oregon, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

During the Emerald Corridor’s “old normal,” from autumn to spring, moisture fell as rain in the valleys and snow on the mountains. But winter snowpacks in the Cascades are already visibly shrinking and glaciers are in retreat.

Less snowpack means lower, and earlier, water flows into rivers and streams. That affects hydropower dams, irrigated agriculture and the lifecycle of salmon and steelhead trout. Winter recreation like skiing takes an economic hit and there may be summer water shortages, even droughts.

Droughts have lasted from May to December, weakening trees, which in turn makes forests more fire-prone. And wildfire smoke can affect the health of people in its path.

Warmer years also mean later fall frosts and earlier springs. Some plants bud early, before the bees or birds that pollinate its flowers have finished their migration. There have been timing shifts for the wine industry, as varietals shift northward, and for the iconic Douglas fir, the mainstay of the Northwest timber industry.

Worst-case scenario, timing mismatches could doom some species to extinction, like checkerspot butterflies.

But in a new normal where nothing is predictable, some years will be unusually wet, with torrential downpours instead of drizzle. That can lead to flooding and the loss of topsoil, which also weakens forests and can trigger landslides. Infrastructure like highways, bridges and dams can be weakened and even destroyed by severe weather or disasters. Cities and towns must spend more money to keep critical systems running.

The ocean faces a host of issues: coastal flooding, beach erosion and sea level rise. The ocean stores more carbon dioxide, so coral, shellfish and other calcium-based life is acidifying. That’s taking a toll on oysters, crabs and other Northwest fisheries.

Warmer water and temperature changes in the ocean water column can disrupt normal sea life. Climate-driven changes have cut oxygen in the water, causing multiple years of dead zones offshore. And lakes, rivers and ponds on land have begun experiencing harmful algae blooms.

Climate change is particularly hard for Native Americans and First Nations people who rely on subsistence fishing. Tribes, poor people and people of color are considered frontline communities because they get hit hardest by bad weather.

The issue of environmental justice figures largely in Emerald Corridor planning to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions, called mitigation, and to live with what can’t be cut, called adaptation.

Trimming emissions at the root

One mitigation approach is to cut emissions at the source. The United States and Canada have lagged on taking national actions, but the Emerald Corridor is one of several areas where localities have stepped up.

Washington, Oregon and their biggest cities

have had mixed success with cutting

emissions, but continue to adopt even

tougher plans to reduce carbon dioxide.

Washington, Oregon and their biggest cities have had mixed success with cutting emissions, but continue to adopt even tougher plans to reduce carbon dioxide.

Washington emissions are down from the state’s 2000 baseline, but recently have trended up over post-recession lows. That prompted Gov. Jay Inslee to push a plan through the Washington legislature in December 2019 that’s been called the toughest in the nation. It would get Washington to net-zero electrification by 2045 — about 30% of the state’s 97.5 million tons of CO2 equivalent greenhouse gases, or MTCO2e.

But it leaves out transportation, which accounts for about 40% of the state’s emissions, and is much harder to cut.

|

| Portland’s climate change adaptations include efforts to encourage residents to bike more through its bike share program, BIKETOWN. Photo: Ian Sane, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Oregon’s most recent emissions reporting from 2018 weighed in at 64.5 MTCO2e, down from a 2000 peak of 73 MTCO2e, but Gov. Kate Brown couldn’t get an ambitious emission reduction plan through the 2019 legislative session when Republicans fled the state capital rather than take a vote on an emissions trading plan that would mandate businesses cut emissions. The state is aiming to hit 40 MTCO2e by 2030.

British Columbia took a different path to mitigation, launching the first North American carbon tax back in 2008. Since then the province has cut emissions by 2%. Much more sparsely populated than either state, B.C.’s latest emissions clocked in at 63.5 MTCO2e, after subtracting carbon offsets.

B.C.’s goal is to get down to about 37 MTCO2e (PDF) by 2030. While the carbon tax has faced some predictable criticism, it has endured. And in 2019, Alberta followed suit, with the Canadian government moving toward a national carbon tax.

The other major way to attack emissions is with a cap-and-trade plan, something the U.S. Congress tried but failed to achieve back in 2009. It behooves journalists to follow the coming debates, which will surface the pros and cons. But if planners take care when creating a carbon tax or cap and trade, either can work.

Adapting to the change

The fallback fix for a warming climate is adaptation — figuring out ways to do things differently to avoid the worst effects of climate change. And Emerald Corridor cities are at the forefront of innovative action.

|

| Adaptation efforts in Vancouver, B.C., include planting an “urban forest.” Above, trees planted at the city’s Olympic Athlete's Village. Photo: DeepRoot, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

An endless number of adaptation stories are possible, touching agriculture, education, public health, real estate, technology, the timber industry and more.

Portland’s climate change adaptations range from aggressive attempts to encourage residents to bike more, to a 2019 revamp of laws that ban single-family zoning in anticipation of an influx of climate refugees from hotter, drier climes.

Adaptation efforts in Vancouver, B.C., include planting an “urban forest” of trees to cope with anticipated heat that by mid-century will transform its climate into that of San Diego. The city also touts its success at redesigning drainage systems to manage future deluges.

Washington state took an idea from Norway in 2018, when it vowed to convert three diesel hogs in its extensive Puget Sound ferry system from fossil fuel to hybrid power by 2023, saving 26% of its fuel consumption.

And on Washington’s coast, a series of bad storms breached a seawall protecting the Quinault Indian Nation’s fishing town of Taholah. The tribe is planning to move most of the town and 700 or so residents to higher ground. As of 2019, the price tag, which has been steadily rising, could hit $100 million. A bill to help fund that cost and other tribal climate adaptation projects passed the U.S. House of Representatives, but as of early 2020 still awaits Senate action.

All levels of Emerald Corridor governments have adaptation plans, but the big problem will be paying to reinvent our way of life. And even if these plans are successful, there’s a good chance it won’t be enough.

The trick then will be finding ways to actually remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere entirely and sequester them somewhere, by everything from planting trees, which store CO2, to sucking greenhouse gases from the air and sequestering them in granite, deep wells or somewhere else. The projects already underway are well worth tracking.

|

| Photo: Lynn Kearney |

Cross-platform writer-producer-editor Christy George has been covering climate change and the environment for 15 years.

She’s currently an itinerant editor for public radio newsrooms from Seattle to Salt Lake City, and has been a reporter-producer for the PBS-TV program, “History Detectives;” the national business show Marketplace Radio; Oregon Public Broadcasting, WGBH-TV; WBUR-FM; and the Boston Herald, where she edited national and foreign news.

Her awards include three Emmys, an Edward R. Murrow award and a Gracie Allen award. She shared in Marketplace’s team Columbia-duPont Silver Baton. She was a 1991 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.

George is also a past SEJ president and board member. She and Rocky Barker are co-chairing SEJ’s conference in Boise, Idaho this coming September.

Advertisement

Advertisement